As we discussed in another post, venture capital firms manage pots of money, called funds, which they invest in start-ups. They charge a high fee for this service (a total of $15 million to manage a $100-million fund over the years, for example). The fee is charged regardless of the success of their investments. This has led some people to believe that VCs focus a lot on raising more and more funds and not so much on making good investments.

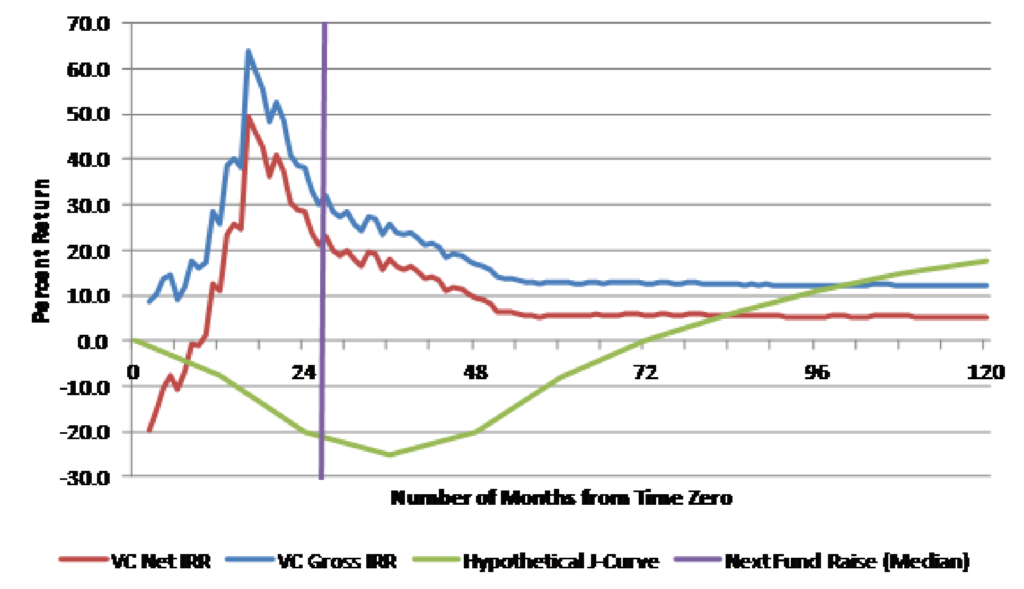

In 2012, the Kauffman Foundation, an American non-profit organization, decided to analyze its past twenty years of investing in VC funds as a limited partner, or LP, meaning that it paid money into the fund without managing it. The foundation published a worrying result: The VC funds in which they invested tended to report to them an exceedingly high performance during the first two years. That coincided with the period during which their managers were trying to raise a new fund (VC firms raise new funds every 2.5 years on average). After the first two years passed, the reported performance dropped dramatically and remained low:

The foundation concluded that fund managers either manipulated their early return figures or only worked hard during the first few months of a fund, which let them promote good figures to others when trying to raise the next fund. The foundation stated, “distressingly, fund managers focus on the front end of a fund’s performance period because that performance drives a successful fundraising outcome in subsequent funds.” Their report also suggested that VCs “write up portfolio company valuations considerably and frequently early in their fund’s life, which results in positive returns” and then performance “retreats precipitously over the remaining term of fund life.” The foundation explained that this tendency became more pronounced after 1995: “our best-performing funds—those launched prior to 1995—did not report peak returns until the sixth or the seventh year of their lives. That pattern began to change in the late ’90s, when peak returns almost always were reported during the fund’s five-year investment period, usually in the first thirty-six months.”

In 2016, a systematic study of 1,074 funds tried to ascertain whether fund managers tried to manipulate their reported returns. The evidence showed that, indeed, at the time of raising their next funds “under-performing fund managers boosted reported returns”; after that, the reported performance dropped sharply. The study showed, however, that overstating performance is counterproductive if overdone, as LPs “see through much of the manipulation.” The authors suggested that the spike in early reported returns may not necessarily be due to intentional manipulation. For example, it could be that after the new fund is raised, VCs “dedicate most of their efforts (and possibly better deals) to the new fund.” Even if that’s the case, the article argues that it still represents a “cost born by LPs in the old fund.”

To understand how this is even possible, let’s see how VCs calculate and their returns. Early on in the life of a fund, most of the investments haven’t been exited yet. So, the VC calculates an estimation of future, or unrealized, gains that it expects to make later on. VCs use different methods to calculate such unrealized gains, and they are all somehow subjective. The VC firm Andreesen Horowitz explains on its website that performing such calculation is “more of an art than a science” and that, to some extent, the resulting figure is “in the eye of the beholder.”

One method to calculate unrealized gains, for example, is to estimate the increase in value of a start-up by comparing it with similar companies that trade in public markets. Andreesen Horowitz explains, “If a portfolio company is generating $100 million of revenue and its ‘comparable’ set of companies are valued in the public markets at 5x revenue, a venture firm would then value the company at $500 million.”

Another method to calculate unrealized gains, probably the most common one today, is to compare the original valuation given by the VC against the valuation given by VCs in the latest investment round. Suppose the first VC invests in a start-up at a valuation of $10 million, and then another VC invests in the same start-up at a valuation of $15 million. The first VC counts that as a 1.5x unrealized gain. The calculation is still somehow subjective as it depends on another VC’s perceived valuation of the start-up—if the latter VC gives the start-up an excessively high valuation, the former VC reports an impressive unrealized gain.

This has led some people to believe that VCs continuously try to jack up valuations in order to inflate unrealized gains. In a critical open letter, a venture capitalist explained, “VCs habitually invest in one another’s companies during later rounds, bidding up rounds to valuations that allow for generous markups on their funds’ performance. These markups, and the paper returns that they suggest, allow VCs to raise subsequent, larger funds, and to enjoy the management fees that those funds generate.” The letter suggests, “Even if paying or marking up sky-high valuations will make it less likely that a fund manager will ever see their share of earned profit, it makes it more likely they’ll get to raise larger funds—and earn enormous management fees. There’s some deep misalignment here…” The author concludes, “the dynamics we’ve entered is, in many ways, creating a dangerous, high-stakes Ponzi scheme.” A Ponzi scheme is a type of fraud in which a con artist generates fake or unsustainable gains for early investors and promotes those gains to lure more and more investors.