By the early 2010s, the internet became massively adopted and much faster than before. This led to the surge of high-growth, Uber-like start-ups. As no other line of business promised such outstanding growth, investors became highly enthusiastic about the sector and tried to find the next “unicorn.” But enthusiasm alone isn’t enough; investors must have access to funds and they must be convinced that the risk is worth taking.

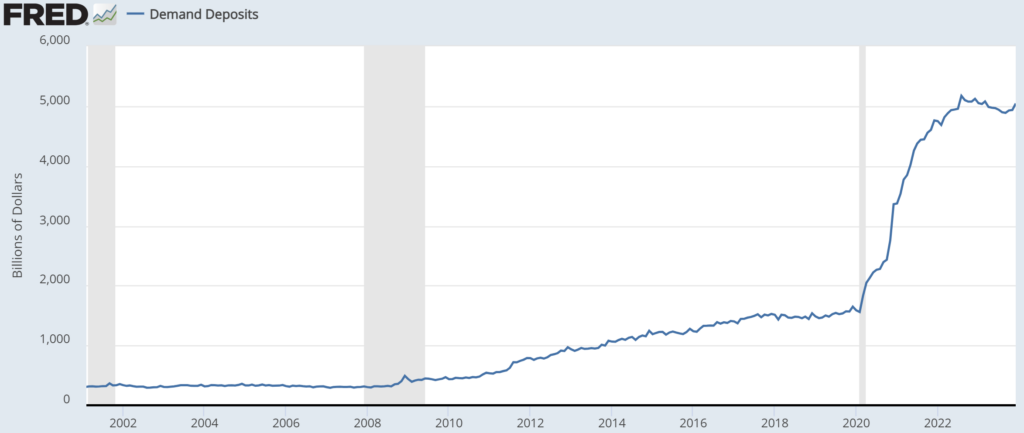

During those years, central banks around the world implemented a package of highly unconventional measures to recover from the 2008 debacle. These were ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) and quantitative easing, both of which intended to make safe investments unappealing and thus encourage investors to take risks. The policies involved creating huge amounts of new money to buy assets directly from financial institutions hoping they’d use the proceeds to buy riskier assets. This may sound like a conspiracy theory, but it was the official intention of the policies. The Bank of England explained, “purchases have been targeted towards long-term assets held by non-bank financial institutions, like insurers and pension funds, who may be encouraged to use the funds to invest in other, riskier assets like corporate bonds and equities.”

Many people believe that these unconventional economic policies provided the fuel that powered the unicorn boom. A technology reporter explains, “With low rates of return from conventional investments, the venture capital ecosystem—one of the few legitimate financial products that tries to offer a thousand-fold return on investment—became flush with cash. Yes, the risk was high, but with interest rates so low it was a risk that was worth taking.” The article added, “Free sushi lunches? That’s a ZIRP phenomenon. Massive discounts for new users? ZIRP phenomenon. Burning money on a metaverse? Definite ZIRP phenomenon.”

According to a Financial Times article, the size of VC investments increased due to “decades of easy money and a lack of decent yields from safer alternatives,” which made VCs go from “small investment rounds involving a few million dollars to gigantic deals involving billions.” This sentiment soon became commonplace; a Wall Street Journal article described the tech boom as a “sugar high of free money,” and a CNBC article stated, “Investors, hungry for yield, poured into the riskiest areas of tech. […] The mania reached a zenith in 2021.”

Low interest rates also provided cheap credit which fueled VC activity. For example, the Silicon Valley Bank, or SVB, provided billions in credit to VC firms to let them invest in start-ups before their investors provided the necessary funds for it, which made the process quicker; almost half of the bank’s loans consisted of this type of credit. Moreover, SVB made it easier for VC firms to pay in their own contributions to the funds they raised (VCs typically invest some of their own money into their funds, typically 1% of the fund, to have more skin in the game); in the ZIRP era, much of their contributions into the funds were borrowed. A Bloomberg article explains, “Partners could turn to SVB for personal loans that gave them additional money to invest alongside their clients even as fund sizes expanded into the billions and fundraising cycles accelerated.”

In 2022, central banks pulled the plug on their unconvential policies and interest rates rose. This caused the collapse of investment into start-ups because safer assets became more appealing. By the end of 2023, investment into start-ups reached a six-year low and stood at 40% of the 2021 spike. Start-ups require continued investment to survive, so the lack of new investments made many of them short of cash and put their future in jeopardy.

As the tech crash unfolded, the Silicon Valley Bank collapsed, start-ups started failing at record rates and the amount of money generated by exits dropped from $797 billion in 2021 to $61.5 billion in 2023. The unicorn boom didn’t turn out as expected.